There is a lot of talk these days about “domain-specific hardware.” It is useful to have a historical perspective to understand this discussion because the pendulum has swung in both directions a couple of times.

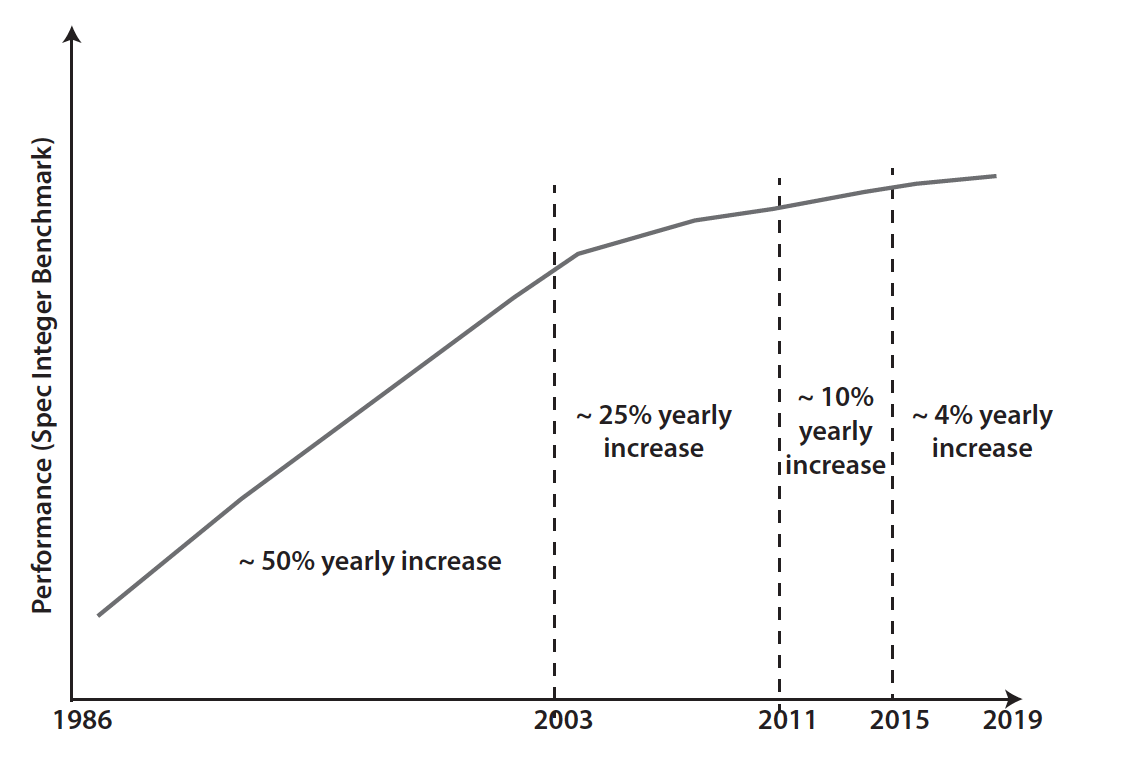

The concept of domain-specific hardware is not new. Back in the 1970s–1980s, at the time of mainframes, the primary CPUs were not fast enough to do both computing and I/O. Coprocessors and I/O offloads were common. During the years 1990 to 2000, we all witnessed a rapid growth of processor performance associated with significant innovation in the processor architecture such as pipelined processor, superscalar processor, speculative execution, and virtualization extensions for speeding up hypervisors. Integrated caches played a big part in this performance boost as well, because processor speeds grew super-linearly as compared to DRAM speeds. All this evolution happened thanks to the capability to shrink the transistor size. In the 2000s, with transistor channel-length becoming sub-micron, it became challenging to continue to increase the speed of the single CPU (or more appropriately core). The SpecINT benchmark that tracks the single-thread performance started to grow only single-digit per year. In 2018, single-thread CPU speed only grew approximately 4 percent per year.

The slowdown in Moore’s law, the end of Dennard scaling, and other technical issues related to the difficulty of further reducing the size of the transistors are causing this slowdown. We will cover them in a future post.

The only effective way to utilize the growing number of transistors was by introducing multicore architectures; that is, putting multiple CPUs on the same chip

In 2010 the pendulum started to swing back. With the introduction of the “cloud,” the cloud providers began to realize that the amount of I/O traffic was growing extremely fast due to the explosion of East-West traffic, storage networking, and applications that are I/O intensive. Implementing network, storage, and security services in the server CPU was consuming too many CPU cycles — these precious CPU cycles needed to be used and billed to users, not to services. The historical period with the mindset: “… we don’t need specialized hardware since CPU speeds continue increasing, CPUs are general-purpose, the software is easy to write …” came to an end with a renewed interest in domain-specific hardware.

Domain-specific hardware is optimized for certain types of data processing tasks, allowing it to perform those tasks way faster and more efficiently than general-purpose CPUs. Graphics processing units (GPUs) are an example of domain-specific hardware. Created to support advanced graphics interfaces, today they are also extensively used for artificial intelligence and machine learning. The key to GPUs’ success is the highly parallel structure that makes them more efficient than CPUs for algorithms that process large blocks of data in parallel and rely on extensive floating-point math computations.

Intel QuickAssist Adapters are an example of domain-specific hardware applied to the field of security. They provide crypto acceleration and compression capabilities.

Another example is Google’s Tensor Processing Unit, an ASIC designed to speedup artificial intelligence operations.

Domain-specific hardware is also starting to appear in the cloud servers, mainly to offload network, storage, and security services from the central server CPU. With the advent of the cloud, and with the proliferation of East-West traffic, implementing these services in software may consume a significant part of the CPU cycles.

In conclusion, now the pendulum points toward domain-specific hardware that has several fields of application and can be a lower cost and lower power utilization alternative to general-purpose CPUs.

A must-read on the topic is “A new golden age for computer architecture “ by John L. Hennessy and David A. Patterson.

This topic is also covered in detail in Chapter 7 of my book Building a Future-Proof Cloud Infrastructure: A Unified Architecture for Network, Security, and Storage Services.