A reasonable question to ask is: “how faster is my application going to run on a new server?”

To answer this question we need to go back to my previous post that explains that starting in 2005, the only effective way to utilize the growing number of transistors we are able to fit in a chip is through the parallelism of a multicore architecture; that is, by putting multiple cores (CPUs) on the same chip.

On some processors, further technology advances permit to run two threads simultaneously on the same core with a technology called hyper-threading. In hyper-threading, a single core is designed with more functional units than it needs on average. For example, it is rare to use all the address generation units and the ALUs for a sustained period unless you’re running highly optimized code. Recognizing this, hyperthreading feeds two streams of execution into a single pipeline that, on average, behaves as two cores.

A two-socket server with 24 cores per socket and hyper-threading can run 2 * 24 * 2 = 96 threads. We will use this server as an example in the rest of this post.

Using multiple threads for a given single task is not as simple as it can first appear. In any computation, there are parts of the job that can run in parallel and components that are serial. Here is where Amdahl’s Law comes into play.

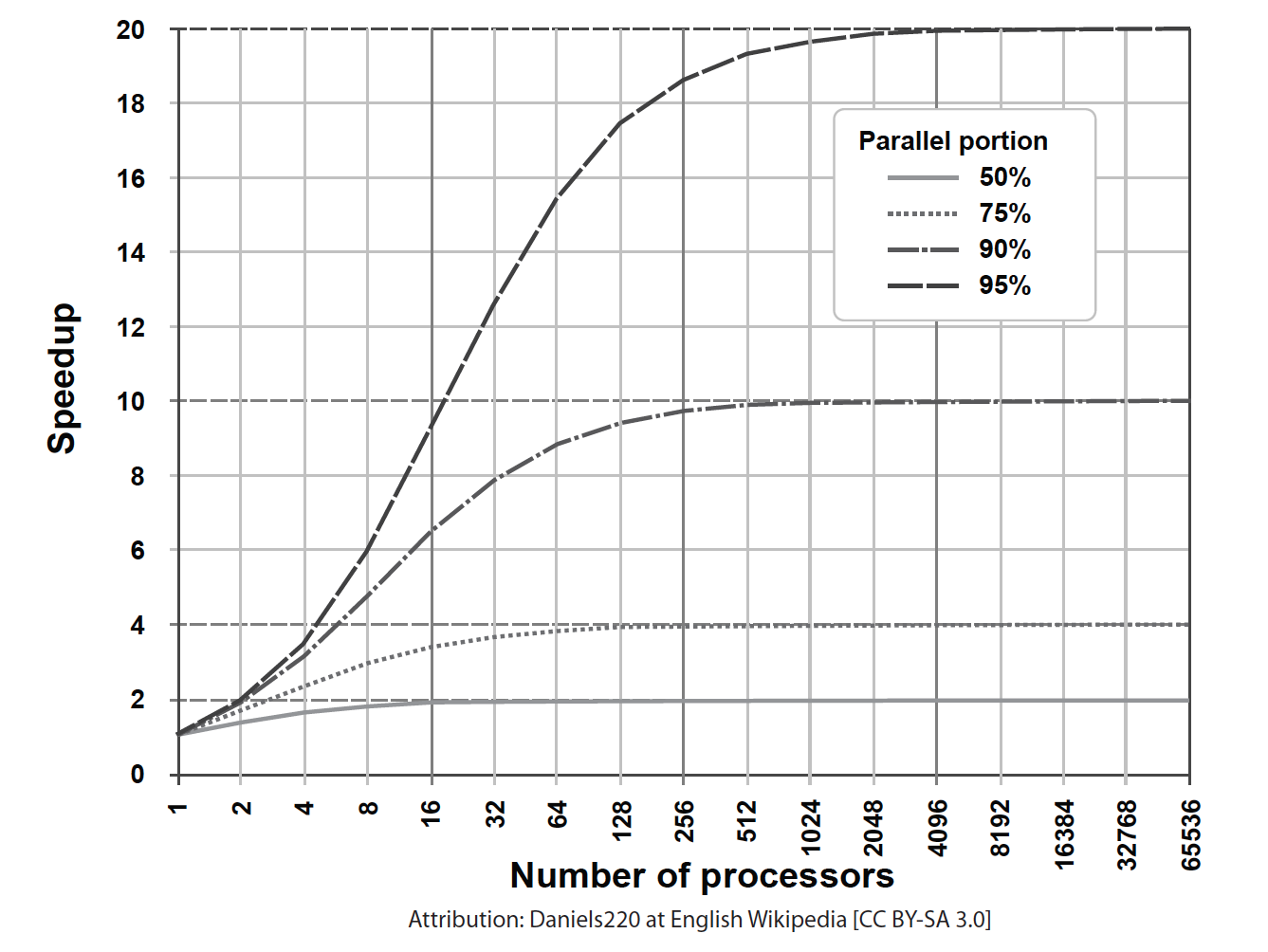

In 1967, computer scientist Gene Amdahl formulated his law to predict the theoretical speedup in the execution of a task when using multiple processors. The “speedup” is defined as the ratio between the execution time with one processor over the execution time with multiple processors. The same law applies to multiple threads. It has two other parameters:

- “N” is the number of threads.

- “p” is the proportion of the program that can be parallelized.

When N approaches infinity, the speedup = 1 / (1 – p).

For example, if 10% of the task is serial (p = 0.9), then the maximum performance benefit from using multiple cores is 10.

The following figure shows possible speedups when the parallel portion of the code is 50%, 75%, 90%, and 95%.

With a 95% parallel portion, the maximum achievable speedup is 20 with 4096 cores, but the difference between 256 cores and 4096 is minimal. Continuing to increase the number of cores produces a diminished return.

A necessary condition for Amdahl’s Law to apply is for an application to be multithreaded, i.e., for different parts of the application to have been organized in different threads so that they can run in parallel.

An excellent example of multi-threaded applications are web servers; both Apache and Nginx, in different ways, can use all the 96 threads of our server, if properly configured. Videogames are another excellent example of multithreaded applications, but they are not Enterprise Applications :-). Databases support multithreading, but often they cannot take advantage of it, since they are I/O-bound, not CPU-bound.

Then there are all the user applications. These are written in languages like PHP, Python, Java, Go, Javascript/node.js, C, etc. None of these languages automatically parallelize your application. It is up to the software engineer to invoke the appropriate multi-thread constructs and parallelize the application. Multithreaded programming and the required synchronization is hard to do right. Some execution environments also limit your multithreading capability: for example, Python is often deployed with GIL that limits the execution to a single thread.

The vast amount of legacy applications and the difficulty to rewrite them with multi-thread support was one of the key reasons for the success of virtualization. A hypervisor is capable of using all the threads of the server: it assigns them to Virtual Machines (VMs). While hypervisors are very flexible in doing so, there are some well-known guidelines that most Enterprises follow. For example, in VMware deployments threads are used by vCPUs and it is common to start with one vCPU per VM and increase as needed, keeping in mind that ratio between the total number of vCPUs allocated over the number of threads available is recommended to not exceed 3:1. No software rewriting is needed since each VM runs a different application.

What is the maximum performance of each application in this environment? It is related to the performance of a single core. Let’s assume that four vCPUs are assigned to a VM, the application is multithreaded and p = 75%. Going back to our figure, the maximum speedup is approximately 2.5 in ideal conditions, more realistically less. This means that the absolute performance of a single thread still matters a lot, even in the presence of multithreading.

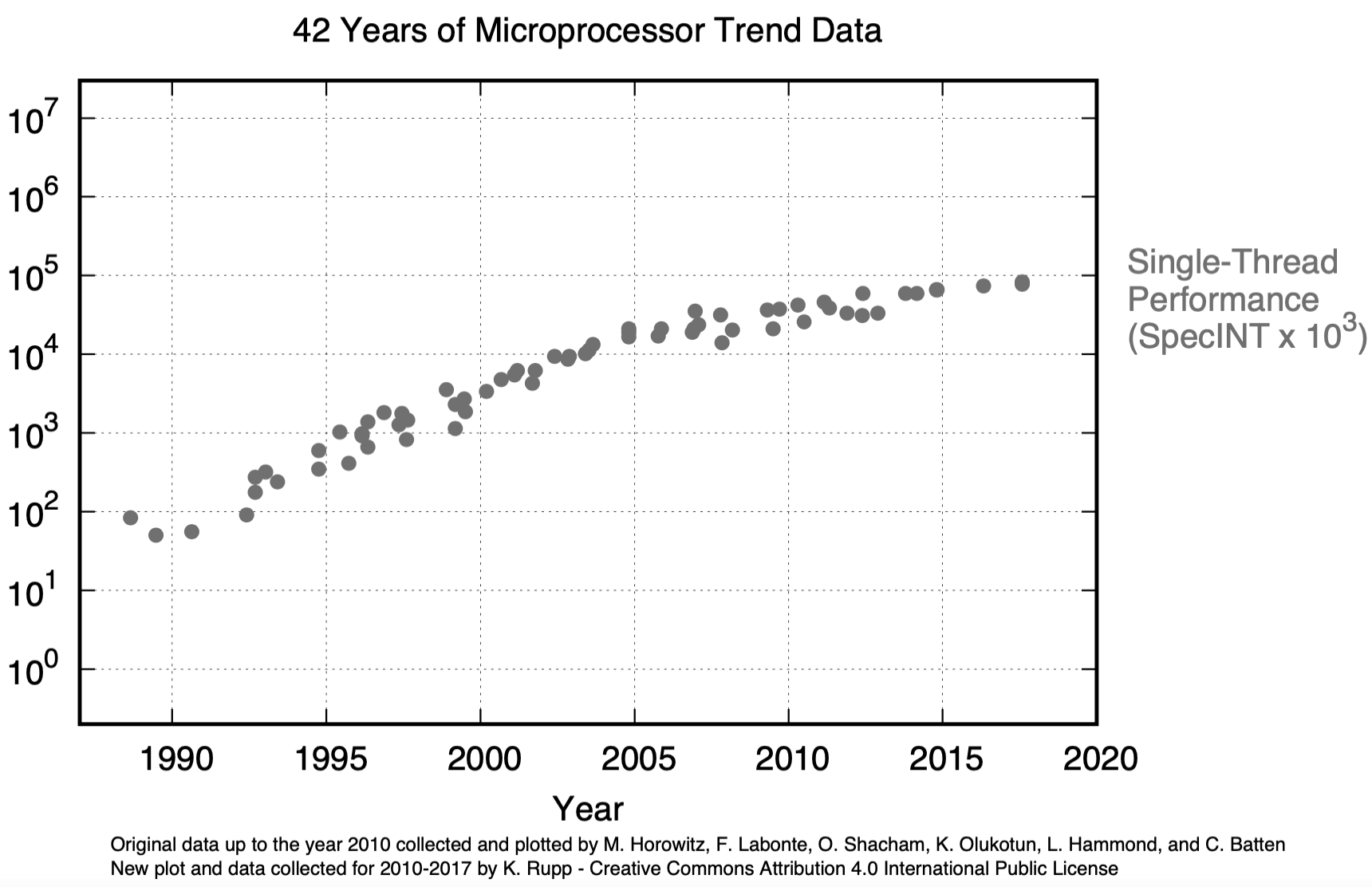

The SpecINT benchmark tracks the single-thread performance. The analysis of objective data is essential to comprehend this trend. M. Horowitz, F. Labonte, O. Shacham, K. Olukotun, L. Hammond, and C. Batten did one of the first significant data collections, but it lacks more recent data. Karl Rupp added the data of the more recent years and published it on GitHub with a Gnu plotting script. The SpecINT resulting from his work is shown in the following figure.

The single-thread performance curve is flattening out. At the current growth rate of 4% per year, it will take 18 years for SpecINT to double.

The answer to the question asked at the beginning of this post is: “Assuming you do not rewrite the application, the maximum speedup you can hope to achieve is the ratio between the SpecINT of the new server and that of the old server.”

If you rewrite the application to be multithreaded you will get an additional speedup that depends on Amdahl’s law, where N is the number of threads usable by the applications; in normal cases I expect this speedup to be in the low single-digit.

Of course, this is true if you use all the new CPU cycles for your applications and do not use them for other purposes like services, such as packet switching, traffic filtering, etc.

Conclusions

In this post, I hope to have proven that it is hard to scale single application performance using more CPU threads. Large core counts on modern servers are best used to scale to a larger number of application instances. This larger number of instances requires a larger number of diverse network, security, and storage services, which in turn can be either provided by domain-specific hardware or be run on server CPU cores. The use of domain-specific hardware for services allows all of the server CPU cores to be deployed directly to the applications, providing maximum server efficiency.

Let me reiterate this: “CPU cycles are precious and need to be used and billed to users, not to services.” Wasting CPU cycles to implement network, storage, and security services is not a good idea. Let’s move these functions to domain-specific hardware.