This question is being asked a lot these days. I am not including any links, but do a search on the Internet, and you will find many matches.

This blog post builds on my previous three:

and it tries to answer this question.

A prominent inspiration for this work was the Hennessy and Patterson Turing Award lecture.

Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and longtime CEO and Chairman of Intel, formulated the original Moore’s Law in 1965. There are different formulations, but the one commonly accepted is the 1975 formulation that states that “transistor count doubles approximately every two years.” Moore’s law is not a law of physics; it is more an empirical observation.

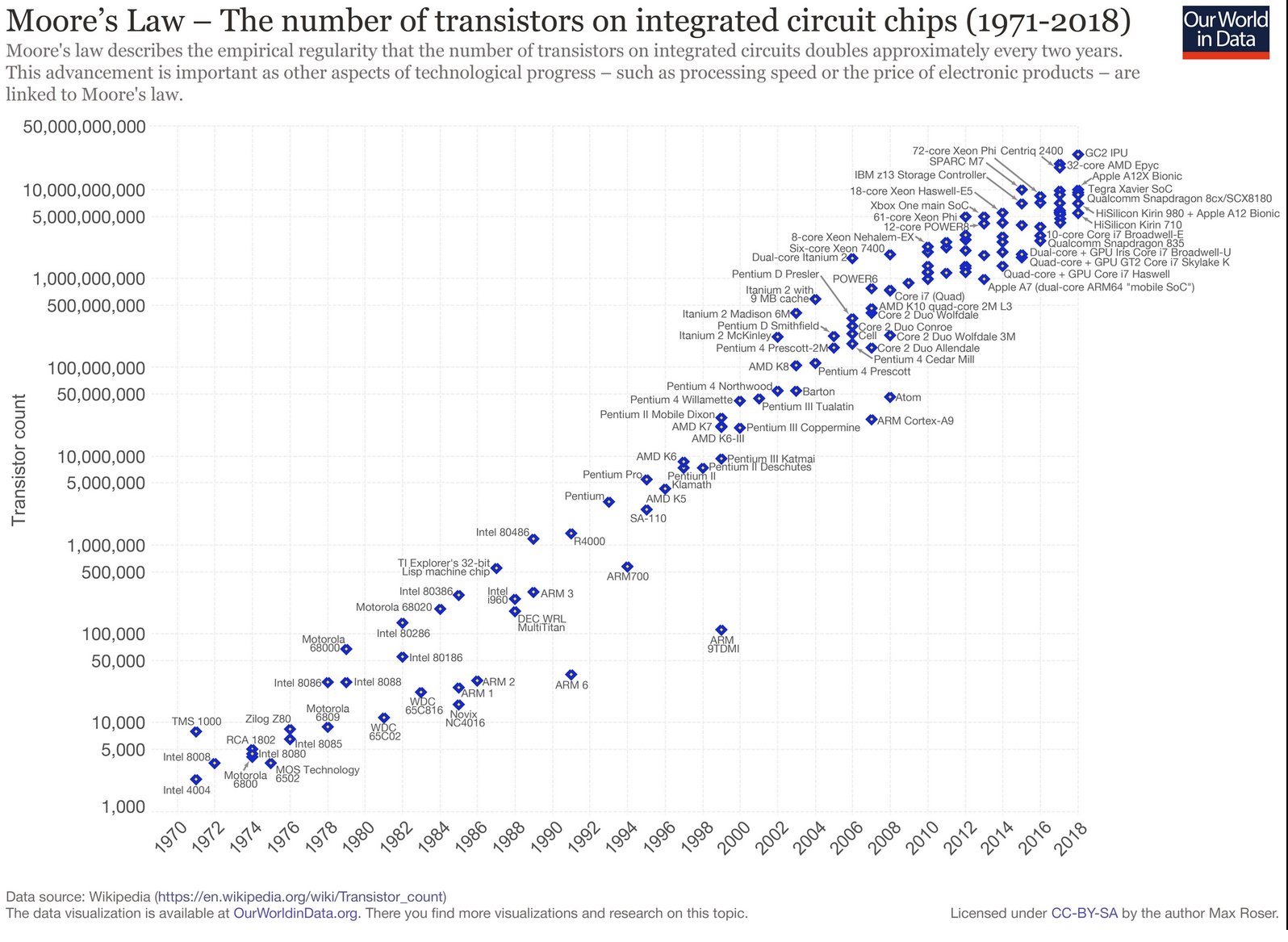

The following figure contains a plot of the transistor count on integrated circuit chips courtesy of Our World in Data.

At first glance, the figure seems to confirm that Moore’s Law is still on track. For example, the AMD Epyc processor and the Graphcore GC2 IPU are two devices that track Moore’s law.

A more specific analysis of Intel processors, which are the dominant processors in large data centers and the cloud, shows a slowdown. In 2015 Intel itself acknowledged a slowdown of Moore’s Law from 2 to 2.5 years. Dennard scaling and other associated power factors play a significant role in this slowdown.

Gordon Moore recently estimated that his law would reach the end of applicability by 2025 because transistors would ultimately reach the limits of miniaturization at the atomic level.

Speaking about processors, one key factor that has allowed processor manufacturers to continue to track Moore’s Law is increasing the number of cores. We have discussed in the post on Amdahl’s law how this increase is relatively easy to use in a virtualized environment, but it does not help much the performance of a single application.

The performance of an individual application is much more related to the performance of an individual core, and it tends to track the SpecINT (Spec Integer) benchmark. In the first post on this series, we discussed how SpecINT is growing only 4% a year, mainly thanks to further improvements in instructions per clock cycle. With this rate of growth, it will take 18 years for the single-thread performance to double!

One other factor that indirectly affects Moore’s law is the size of the die. With the reduction of the channel length, the cost of the die continues to increase since the yield decreases. Compared to the 45 nm process, the 16 nm process more than doubles the cost/mm² and the 7 nm process nearly doubles that to 4x the cost per yielded mm².

AMD and Intel have started using chiplets. The AMD Epic processor, and Intel’s mobile client platform, code-named “Lakefield,” are examples of devices that use chiplets.

Instead of building new processors from a single large die, the processor is split into multiple chiplets that are assembled on a silicon interposer or other advanced packaging technologies. You can think of these chiplets as modular blocks designed to be assembled together. You can imagine:

- functional partitioning: one chiplet for compute, one for storage, one for I/O, etc.

- separation of core logic processes, from I/O device logic, and SERDES.

- data partitioning: 4 cores per chiplet.

This is different from assembling multiple chips on a mother-board, since the packaging technology has much lower parasitic parameters and allows speeds orders of magnitude higher. The yield of the chiplets is much higher since their silicon area is smaller and therefore the overall cost per mm² is lower.

While chiplets help with modularity, cost, and time to market, they don’t help much, or may be slightly worse, in terms of power and power density, which depends on the total number of transistors. Nonetheless they are one way companies try to cope with the slowdown of Moore’s Law.

Is Moore’s Law Dead or Not?

At the time of writing, for some devices, the transistor count still follows the exponential growth line predicted by Gordon Moore, but it has slowed down for general-purpose processors.

Continuing to reduce transistor channel length steadily will be challenging since the channel length is approaching the size of atoms; this is a primary barrier. Gordon Moore and other analysts expect Moore’s law to end around 2025.

Amdahl’s Law and Dennard Scaling are severely impacting the performance growth of a single application, and that is often confused with Moore’s Law and leads to the claim of some analysts that Moore’s Law is dead.

Finally, there is Moore’s second law (also called Rock’s law) that states that at the cost of a semiconductor chip fabrication plant doubles every four years. These fabrication plants are so capital-intensive (currently around 10 billion dollars) that availability of capital may limit the growth, even before the first Moore’s law dies.

Many companies are working to extend the life of Moore’s law, for example, we have discussed the chiplet approach. Another idea to delay the death of Moore’s law is by scaling across functions (i.e., core server application functions, storage functions, network functions) using domain specific processing to increase server efficiency in a way that is less impacted by Dennard scaling. Physically separate chips for separate functions are easier to cool than monolithic chips.